fig. 75a

CHAPTER 3: History to 1800

3.5 The Baroque, Rococo and Classical Periods 1600-1800

3.5.1 The west

1.2. Higher cultures in the 17th & 18th centuries: Romance language-area

Documentary evidence: 3 of 14

[135b]

|

fig. 75a |

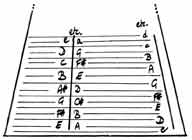

A fascinating practical view was provided in his Musurgia Universalis of 1650 by Athanasius Kircher (162), a Jesuit professor of natural science in Germany, who settled in Rome in 1637 (163). His treatment of the dulcimer occupies little more than a page, compared with the extended discussions of lutes and viols, for instance, but his remarks (fig.75a) are certainly worth a tentative paraphrase here:

'Psalterium, a stringed instrument; if matched with a skilled hand, is like no other, whether the comparison be of harmonic variety, or the remarkable loveliness of its harmonious sounds. As the instrument is reconstructed sonorously by skilled craftsmen, they double or treble the strings, or rather they usually quadruplicate them because of the size of the instrument, such that the single strings [i.e. courses] are tightened to one particular note in unison. The outstanding musicus(164) D[on] Gio[vanniJ Maria Canarius here in Rome has an instrument of this kind, consisting of 148 strings; he plays it so skilfully, that the remarkably lovely and unusual harmonia (171) which it makes to the ears is indescribable: similarly and most properly do the most skilled masters practise their playing to perfection. Moreover, there is no little difficulty involved in making the thing sound coherently, as it is played (pulsetur, 'beaten') with prepared quill stubs, and so this kind of playing requires a dextrous and agile hand; at the same time as the strings are excited by the quill stubs, the next moment the remaining fingers quieten the tremor of the excited strings by a soft touch, to avoid confusing sounds.'

He gave a diagram (fig.75a) which, although detailed, poses a few problems.

Note firstly that upper-case letters are used in three different ways:

The second point to notice is that although the diagram shows the first and second series as having ranges of three-octaves-and-a-semitone, and the third series as having three-octaves-and-a-major-third, Kircher describes them verbally as having one note more than this, three-octaves-and-a-ditone (major third) and three-octaves-and-a-fourth, respectively.

A third problem is that, assuming the central line to represent a bridge, each string is divided into two portions, giving only two series of notes, not three. We should presumably take the diagram to be a simplification of the most common system, of strings alternately divided and undivided, only half the total number of courses having been shown; and presumably the first series is that which is usually played immediately to the left of the bridge, not at the far left as shown. There could be other interpretations, of course, but since an interpretation following common practice produces a feasible result there seems little point in looking further at present: if this is a correct interpretation, the first series can be seen to be a fifth above the second series (or a fourth below it, of course): a few of the intervals are augmented or diminished, but the chessmen bridges normal on Italian salterii provide for such flexibility even though they are not shown. If we consider the second and third series to be provided by separate sets of strings, we find a fifth between adjacent courses, and the diagram may be represented thus:

fig.75b

- Kircher's psalterium: reconstructed tuning diagram

If we assume the most common bridging and stringing arrangement, with the highest notes on the left and the lowest on the right, the available notes may be shown in staff notation and with letter-names, thus:

fig.75c - Kircher's psalterium: reconstructed tuning in staff notation, letter-names and tablature letters

The tablature itself, consisting only of a single line, contrasts with the many pages of ensemble music for the more 'mainstream' instruments; yet it is particularly interesting, for it is the only example found of a tablature specifically designed for dulcimer (165): and indeed it seems likely that it was devised specially for this one work. The three series of notes already discussed are represented by three lines, and the courses of each series to be played are shown by letters on the appropriate lines. The minims and crotchets show when each note is to be plucked:

"Notae vero musicales significant tempus cantilenae, quod pulsare debet: sed haec vulgo nota sunt"(166):

'On the other hand, the musical notes show the tempus of the cantilena ['soothing song'] , as it should be played: but these things are generally well-known' (22).

The notes do not show duration, incidentally, since in playing, each note is normally allowed to sound until it dies away - hence the 'confusing sounds' already referred to.

fig.75d - Kircher's psalterium tablature (166) (copy)

The system uses elements of both French and Spanish tablatures for fretted instruments (for a brief survey see, e.g. Willi Apel, Notation of Polyphonic Music) with the necessary adaptations for an instrument having open strings, of course. Following the principle of showing each note as lasting for as long as it makes harmonic sense, Kircher's snippet may be transcribed thus:

fig.75e - Kircher's psalterium tablature: transcription

Even as a fragment to illustrate a working principle the music is perhaps a little ungainly. One might imagine that the occasional note was misplaced by one space or line - a common enough error - at some stage before it was intabulated, and the following result might then be considered more satisfying:

fig.75f - Kircher's psalterium tablature: amended transcription

A reader without a dulcimer handy might gain an approximation of the effect by playing the piece lightly on a piano with the sustaining pedal held down throughout; it should be borne in mind, of course, that the overall resonance of a modern piano is likely to be much greater than was that of a l7thC. psalterio, even one as large as that of Don Canarius with its 148 strings.

Kircher's synopsis instrumentorum polychordum is also fascinating: the harps and psalteria form group 4, "Quae omni abaco, & manubrio destitua utriusq. manus ministerio imediatè sonantus"(168): 'those lacking all abacus (keyboard) and handle [fingerboard], and are sounded immediately through the ministration of either hand' (22). The details of the synopsis are beyond the scope of the present study, but offer absorbing material for a study of the etymology of music and instruments, and the concepts engendered by various names: the connection with the classification used in this work is also interesting (chapter 1 and supplement 1).

|

|